Appreciate the Disaggregated Dollar

More on:

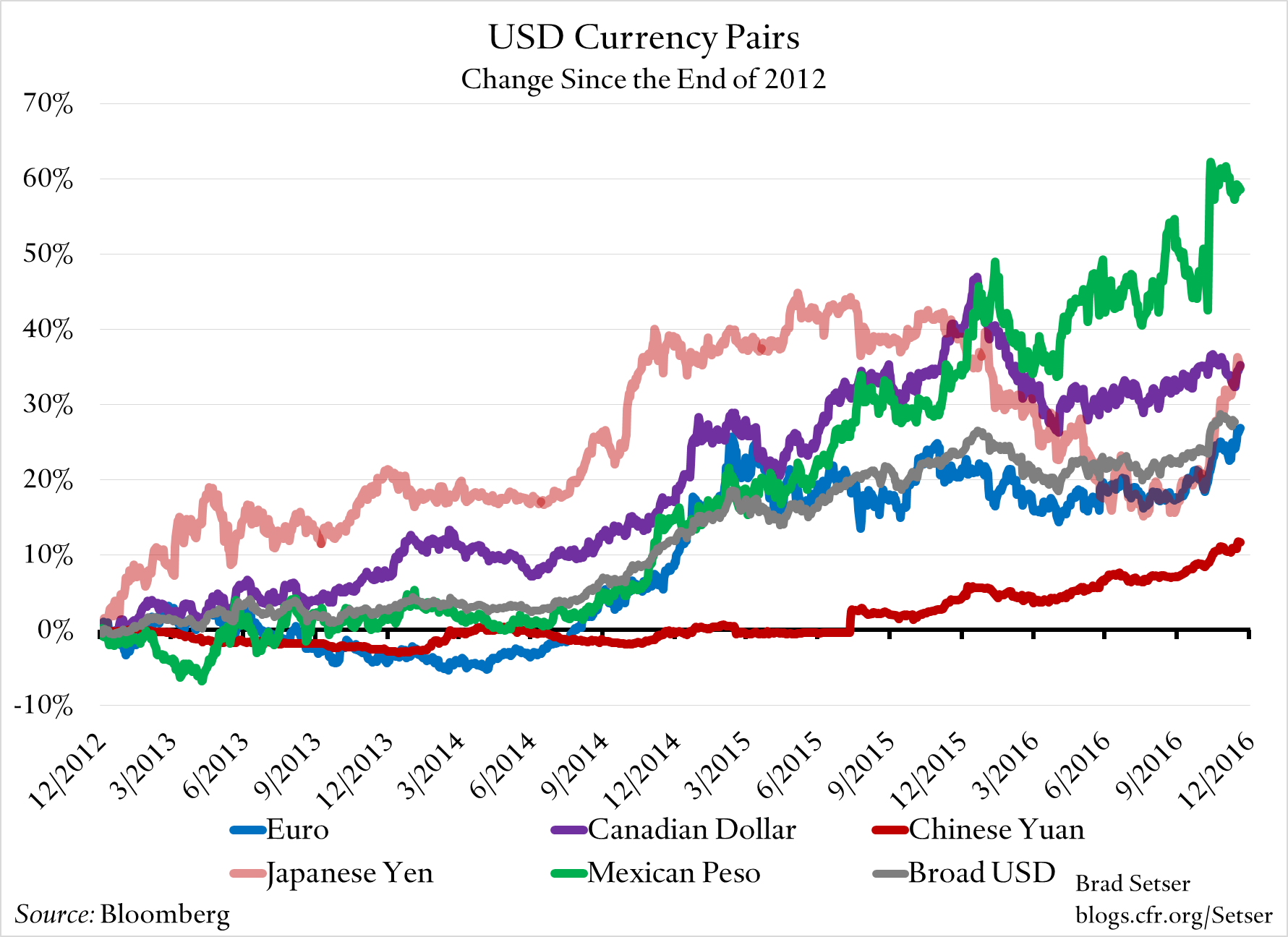

The broad dollar is now up well over 20 percent since the end of 2012. The vast bulk of the move occurred in the last two and a half years.

The dollar has essentially reversed its 2006 to 2013 period of sustained dollar weakness (tied to the weakness of the U.S. economy, the size of the U.S. trade deficit, and the Fed’s willingness to act to ease U.S. monetary conditions at a time when the ECB was stubbornly resistant to monetary easing).

And in some sense we have already seen some of the results play out.

- U.S. export growth has slowed (though U.S. import growth has remained fairly subdued, particularly in 2016—moderating the impact of net trade on output)

- China decided that it couldn’t continue to manage its currency primarily against the dollar, but only after (essentially) following the dollar up in 2014. The transition though to a basket peg—if that is what managing with reference to a basket means—hasn’t been clean. After the 2014 appreciation, it seems China wanted to use the transition to a new regime to bring the yuan down a bit against the basket. One big question is whether China thinks the 10 percent depreciation against the basket that it carried out over the past year and a half is enough.

- Many, but not all, oil exporters that maintained heavily managed currencies against the dollar let their currencies depreciate. Saudi Arabia is of course the most important exception.

- And—illustrating the impact of the reserves that were accumulated by most emerging economies over the last decade plus—the big dollar appreciation has yet to trigger a major emerging market default. Brazil and Russia have both weathered large depreciations and recessions without default.

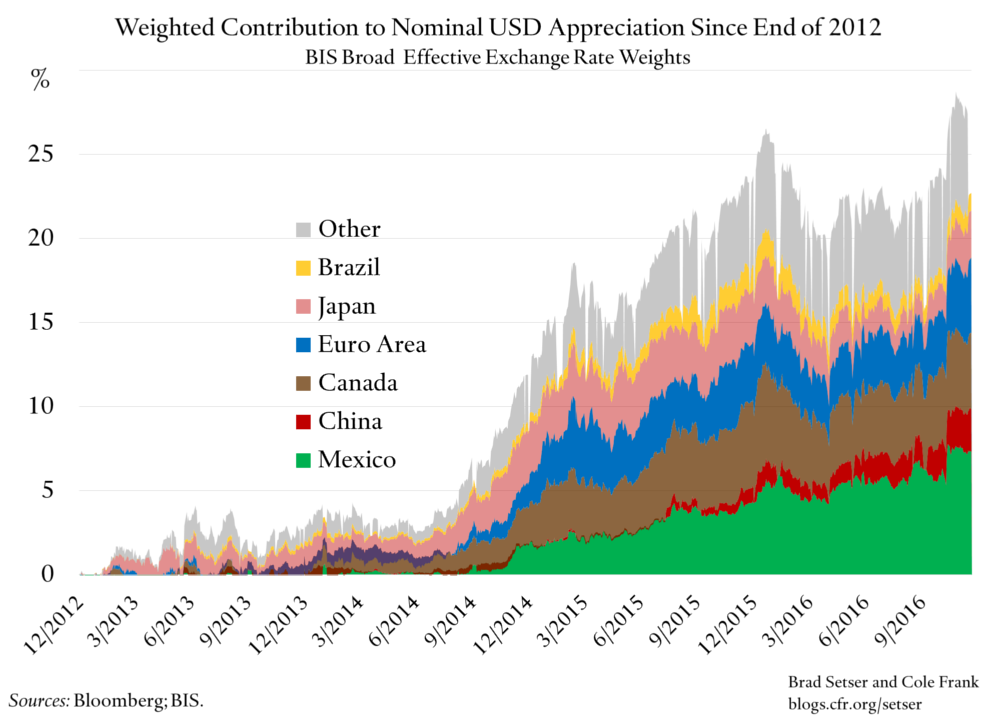

One particularity of the United States is that two of its closest trading partners—Canada and Mexico—are both major oil producers and large exporters of manufactures. The value of both the Mexican peso and the Canadian dollar both really matter for U.S. trade, and both are to a degree influenced by the price of oil. The following graph, prepared by Cole Frank of the Council on Foreign Relations, disaggregates the contribution of different currencies to the move in the trade-weighted (nominal) dollar.

The G3 currencies (dollar, euro, and yen) naturally tend to attract a lot of attention. Especially with the euro approaching parity against the dollar. But, I at least, find it useful to remind myself how much Mexico, Canada, and China matter for the broad dollar index (and thus U.S. trade).

Given that China and emerging Asian currencies that tend to ultimately move in a somewhat correlated way with China are about 30 percent of the trade-weighted dollar index, it seems obvious that the U.S. would face a significant real shock if the move in China’s currency ends up matching the moves in some other key currencies over the last four years.

China has a bigger weight in the index than either Mexico or Canada, and China and the other emerging Asian economies combined have a somewhat larger weight than Mexico and Canada combined. Yet so far China’s contribution to the overall dollar move has been modest.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store